|

|

| Stalag VII A: The Liberation |

|

©

Jim Lankford: THE LIBERATION OF VII A Contact the author for permission to use images and text from this essay. |

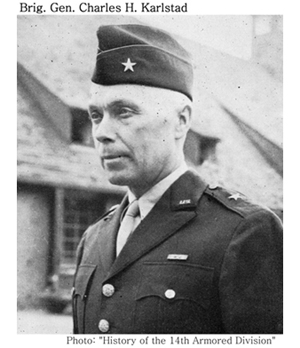

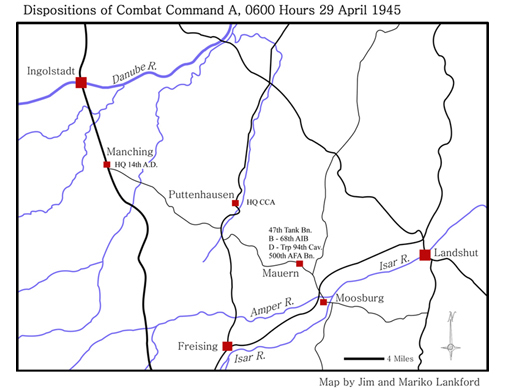

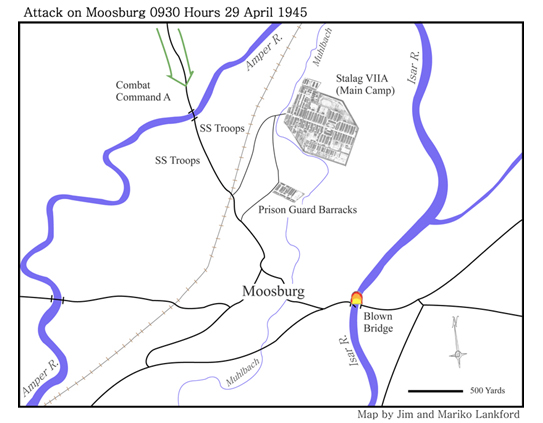

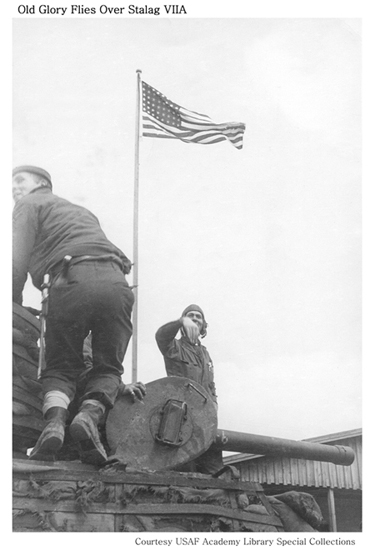

Note: An edited version of this article was published by the Army Historical Foundation in the Fall 2005 issue of On Point: The Journal of Army History. On 30 April, 1945 the New York Times reported; "Huge Prison Camp Liberated...27,000 American and British prisoners of war at a large camp at Moosburg." The report was correct, the camp was huge, but it was also wrong. The following day, the Times printed a correction; "The Fourteenth Armored Division liberated 110,000 Allied prisoners of war at Stalag 7A at Moosburg, instead of the 27,000 prisoners previously reported. This was Germany's largest prisoner of war camp."[1]  On 28 April the 14th Armored Division crossed the Danube River at Ingolstadt, and passed through the 86th Infantry Division, which had established the bridgehead on the previous day, with the mission of securing crossings of the Isar River at Moosburg and Landshut. Combat Command A (CCA) was on the right of the division's line of advance, Combat Command R (CCR) was on the left, and Combat Command B (CCB) was in reserve. Large numbers of German troops were falling back on Moosburg to cross the river. Among them were the remnants of the 17th SS Panzer Grenadier and 719th Infantry Divisions.[2] It was, as it had been for much of the way across France and Germany, a race to capture a crucial bridge before retreating German units got safely to the other side, and blew it up in the faces of the oncoming Americans. Under its commanding officer, Brig. Gen. C.H. Karlstad, CCA moved quickly towards Moosburg. The order of battle consisted of the 47th Tank Bn., the 500th Armored Field Artillery Bn., D Troop, 94th Cavalry Squadron, C Company, 125th Armored Engineers Bn., B Company, 68th Armored Infantry Bn, and B Battery, 398th Antiaircraft Bn.[3] Total strength of the command was about 1,750 men, including support units.[4] With only one company of infantry at its disposal, the combat command was significantly under strength in infantry.  The combat command advanced nearly 50 miles on the 28th, against sporadic resistance. CCA Headquarters settled in for the night at Puttenhausen at 2300 hours. The main force, including the 47th Tank Bn. and the infantry of B-68, was eight miles to the southeast at Mauern. They were only four miles from Moosburg.[5] The entry into Mauren had not been an easy one. Not long before midnight, the infantry went in ahead of the tanks to clear the town, and were ambushed by SS soldiers using machineguns and automatic antiaircraft guns. The enemy resistance was eliminated in a short, but intense fire fight. B-68 lost several men before the town was finally secured.[6] During the early morning hours of the 29th, a car approached a roadblock on the southeast side of Mauren from the direction of Moosburg. The car was not fired on as it was seen to be flying a white flag. In the car were four men who asked to speak with a senior officer. They were escorted to Lt. Col. James W. Lann, the commanding officer of the 47th Tank Bn.[7] The party included a representative of the Swiss Red Cross, a major in the SS, Col. Paul S. Goode (U.S. Army), and Group Captain Willets (RAF).[8] The latter two were the senior American and British officers from Stalag VIIA, a prisoner of war camp near Moosburg. The SS major carried a written proposal from the area commander, which he was to present to the commanding officer of the American force. After a brief discussion, Lt. Col. Lann escorted the group to Puttenhausen to meet with Gen. Karlstad.  The combat command's intelligence officer (S-2), Major Daniel Gentry, was on duty in CCA headquarters when Lt. Col. Lann arrived. Lt. Col. Lann went in, leaving the delegates to wait outside. He told Major Gentry about the delegation, and asked if Gen. Karlstad was available. Major Gentry told him that the general had just awakened, and would be in the command post shortly. Gen. Karlstad walked in a few minutes later, and heard Lt. Col. Lann's report before the delegation was brought in. The delegation entered the command post just before 0600. Col. Goode and Gen. Karlstad immediately recognized each other. They were old friends, and greeted each other warmly by their first names. Major Gentry was somewhat dismayed at Col. Goode's appearance. His jacket was not the right color, and was made of a coarse, poor quality wool. The rest of his uniform was badly worn, and in generally poor condition. Col. Goode was wearing a single insignia of rank which was pinned to his jacket collar. It was crude, and appeared to have been cut from a piece of tin. In contrast, Group Captain Kellet's uniform was in excellent condition. He was even carrying an officer's swagger stick. After the introductions, the Red Cross representative and the SS major discussed the German proposal with Gen. Karlstad. Col. Goode and Group Captain Willets did not take part in the discussion, and for the most part, spent their time talking with various officers in the command post. At some point during the discussions, Col. Goode left the room to get something to eat. Since it was actively engaged in combat operations, and far ahead of Division Trains, the combat command was on C Rations. Learning that Col. Goode was a prisoner of war, some the men, who had acquired a few fresh eggs for their personal use, cooked him a breakfast of fried eggs, bacon, and toast. The German proposal was written in English. It called for an armistice in the area around Moosburg, using as a reason, the presence of a large prisoner of war camp. It also called "...for the creation of a neutral zone surrounding Moosburg, all movement of allied troops in the general vicinity of Moosburg to stop while representatives of the Allied and German governments conferred on the disposition of the Allied prisoners of war in that vicinity." Prior to this, no one in the division had even known there was a prison camp at Moosburg, much less how large it was.[9] On learning the details of the German proposal, Gen. Karlstad sent a radio message to division headquarters at Manching, asking the division commander, Maj. Gen. Albert C. Smith for instructions. It was clear that if accepted, the proposal would prevent CCA from capturing the bridge across the Isar River, as it was located within the proposed "neutral zone." It would also give the retreating Germans more time to withdraw across the river, and provided them with the opportunity to move at least some of the Allied prisoners with them. Gen. Smith rejected the proposal, and added a demand for the unconditional surrender of all German troops at Moosburg. Gen. Karlstad relayed Gen. Smith's response to the SS major. He did not issue a deadline by which the German commander must respond or make any allowances that might further delay the combat command in the fulfillment of its mission. After the delegation left the command post to return to Moosburg, Gen. Karlstad issued orders for the attack on Moosburg to proceed. In his message, Gen. Smith had ordered Gen. Karlstad to: "Lead your troops into Moosburg." The order was unusual, and not in keeping with the way Gen. Smith typically worded orders to his officers. As a result, there was some discussion in the command post regarding Gen. Smith's meaning. Gen. Karlstad decided that it was his superior's intention that he was to actually lead the attack. He subsequently climbed into his peep (jeep), along with his aide, 2nd Lt. William J. Hodges, and accompanied by Lt. John Sawyer of D Troop, drove to the 47th Tank Bn. headquarters at Mauren.[10] There he joined Lt. Col. Lann, and with him, moved with the tank battalion in its attack on Moosburg.  There was no further discussion regarding the prison camp or its capture. The combat command was to continue with its primary mission of seizing a useable bridge across the Isar River.[11] Regardless, the liberation and security of the Allied prisoners of war was clearly of great importance, and the combat command would take the necessary steps to ensure this was accomplished. The men of the division had done this sort of thing before. Three weeks earlier, they had fought their way into Hammelburg to liberate Stalag XIIIC and Oflag XIIIB.[12] As soon as its units were in position, CCA attacked down the main road between Mauern and Moosburg. The infantry platoons of B-68 were attached to the tank companies. The tanks of C-47, along with the 2nd platoon of B-68, were in the lead. They were followed by the tanks of B-47, with A-47 in support. Simultaneously, a platoon of tanks from C-47, and a platoon of infantry executed a flanking maneuver on the right of the main line of attack. Lt. Col. Lann took command of the main force, and Major Alton S. Kircher, the 47th's Operations Officer (S-3), led the flanking force.[13] Since there were so many Allied prisoners of war in the area, the risk of casualties due to "friendly fire" was high. As a result, the attack was made without the powerful guns of the 500th Armored Field Artillery Bn.[14] The main force advanced without meeting any resistance to a point about 1 mile west of Moosburg, where the road crossed the Amper River. It was there, on the east bank of the stream, that the SS decided to make their stand.[15] The first tank to move across the bridge came under intense small arms fire from SS troops located on the far side of the stream. The infantry quickly took cover behind the tank, while the rest of the tanks and infantry took up positions along the bank of the river, and opened fire on the enemy positions. Several infantrymen on the bridge were wounded by the first bursts of enemy fire. After they were evacuated from the bridge, the American tanks and infantry moved forward into the fight.[16] The SS fought from dug-in positions in the fields leading to the town, and from positions behind a railroad embankment on the American's left flank. The embankment was about 500 yards from the bridge, and lay on a direct line between it and the prison camp.[17] Resistance was stiff, even fanatic, but short lived. The SS had no tanks or antitank guns, and were armed only with small arms, machineguns, mortars, and panzerfausts. The battle-hardened Americans fought their way through the SS positions in the fields with relative ease, while returning the fire coming from the railroad embankment. The Germans surrendered when the Americans reached the edge of Moosburg, and by 1030, "... the SS were lying dead in their foxholes or going to the rear a prisoner...."[18] The tanks of C-47, and their supporting infantry, moved out at once to seize the bridge across the Isar. They raced through the streets at 20 miles an hour without meeting any resistance. On arriving at the bridge, the force came under small arms and machinegun fire from the far side of the river. The infantry dismounted from the tanks, and returned fire while the lead tank rolled out onto the bridge. Just as the tank got fully onto the bridge, the Germans set off the demolition charge, and the center of the bridge disappeared in a massive explosion. The section of the span under the tank began tilting precariously down, towards the water. The driver brought his 32 ton vehicle to a halt, and slammed its transmission into reverse. With the tank's treads spinning, he skillfully backed the tank off the tilting portion of the bridge, and onto firm ground, before it slid into the river.[19]  Col. Goode and Group Captain Willets had arrived back at the camp shortly before the engagement at the Amper River bridge. They told their fellow prisoners that an armored unit was coming to free them, and while the German resistance was expected to be light, they should keep their heads down. The prisoners and guards watched as the SS took up defensive positions in the area. It was not long before the sounds of battle came from the distance. The fight for Moosburg was underway. Fire from the American tanks and infantry, aimed at the SS who were firing from behind the railroad embankment, came into the camp. Prisoners and guards alike hurriedly sought cover in ditches, under buildings, and behind brick walls[20]. Adding to the commotion was the sound of the demolition charges exploding as the Germans destroyed the bridge across the Isar. As soon as it had started, it was over. The firing ceased except for the occasional sounds of small arms and machinegun fire from the direction of the bridge. While the effort to capture the bridge was underway, Gen. Karlstad went into Moosburg with the main body of his force. "Large numbers of German prisoners were being rounded up by Lann's tank and infantry platoons, including one large group that stated it was the guard of the prison camp." Gen. Karlstad and his staff questioned some of the German officers regarding the prison camp, "... and selected a German captain to act as his guide to the prison camp."[21] Gen. Karlstad.... With 1st Lieutenant Joseph P. Luby of the 68th Armored Infantry Battalion and 2nd Lieutenant William J. Hodges, and their 3 "Peep Drivers", this party started out across town, guided by the German captain. As this little convoy, carrying one mounted .30 caliber machine-gun, approached the camp gate, the alarming sight of a large number of armed "Heinies" in the outer yard of the great camp was noted, but Lt. Luby took exactly the right action. Without slackening his speed but with both hands on the business end of his machine-gun he rolled into the middle of the German formation, brought his peep to a sudden halt and called "Actung." [sic] The German guard of 240 men was ordered to line up and to drop their weapons in front of them. The two young officers and 3 drivers went rapidly down the line receiving the pistol belts from officers and making a quick search of arms in the pockets of the guards.[22] Moments later, a battle-scarred medium tank joined them at the main gate. Still others, carrying infantrymen on their backs, took up positions outside the camp. Gen. Karlstad called for the German Camp commander [Col. Otto Burger] and received an unconditional surrender of the German garrison and the camp. The first allied prisoners to present themselves were Group Captain Willets and Colonel Goode, .... In a few moments an enterprising American produced a United States Flag – from where, perhaps only he knew – and amid thunderous cheers from the prisoners, ran it to the top of the camp flag pole. It was a dramatic moment."[23]

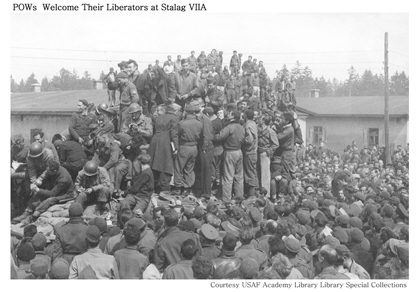

The liberators had arrived, and the prisoners were now, finally safe. As the realization of this sank in: Scenes of the wildest rejoicing accompanied the tanks as they crashed through the double 10-foot wire fences of the prison camps. There were Norwegians, Brazilians, French, Poles, Dutch, Greeks, Rumanians, Bulgars. There were Americans, Russians, Serbs, Italians, New Zealanders, South Africans, Australians, British, Canadians, - men from every nation fighting the Nazis. There were officers and men. Twenty-seven Russian Generals, sons of four American Generals. There were men and women in the prison camps .... There were men of every rank and every branch of service, there were war correspondents and radio men.[24] They rushed to greet their liberators. So many flowed around and over the tanks, peeps, and half-tracks, that even the huge Sherman tanks completely disappeared beneath a mass of jubilating humanity.

Here the division found many of its own soldiers, some of whom had been listed as Missing in Action since mid-November when the division first went into combat. The tankers of C Company were thrilled to see eight of their comrades who had been captured the previous January. Tech 5 Floyd G. Mahoney, also of C Company, "... was particularly overjoyed upon finding that his son, an air corps lieutenant, was a prisoner there."[26] Most of the American soldiers who fought at Moosburg never actually saw the prison camp. They did not have much time to join in the celebrations or even to reflect on what they had accomplished. That would come later. That afternoon the infantry of B-68 crossed the Isar on a footbridge built by the engineers, and began patrolling the far side of the river. They took some more casualties when they came under sporadic fire from small arms, mortars, self-propelled guns, and artillery.[27] The rest of the combat command set up a defensive perimeter around Moosburg, and began patrolling the west bank of the Isar. Virtually everyone became involved in the task of rounding up the thousands of German soldiers who had been trapped in the area when the bridge was destroyed. Even Gen. Smith brought in a prisoner. Early in the afternoon he arrived at the CCA command post in Moosburg with an SS major riding on the hood of his peep. In one of those strange coincidences of war, it was the same SS major who had led the delegation to CCA headquarters early that morning.[28] CCA failed in its mission to capture a bridge across the Isar, but this was soon overshadowed by the magnitude of the liberation of Stalag VIIA. It did not hold 27,000 prisoners of war, as was originally reported, but 110,000.[29] Among them were 30,000 American soldiers, sailors, and airmen![30] Word of the massive liberation spread quickly, and even General Patton visited the prison camp with an entourage of high ranking officers.[31] Combat Command B closed in on Moosburg that afternoon, along with elements of the 395th Regiment. The following night they crossed the Isar River on a bridge which had been built by C-125th Armored Engineers Bn. and the 998th Treadway Bridge Company. "... tanks and endless lines of silent infantrymen, ..., faces set and hardly seeing the weaving scene about them, eyes straight ahead ...." moved forward, across the Isar River, and deeper into Germany.[32] Behind them the war was over, but ahead, although it was entering its final days, the war was still very much alive. For the soldiers of the 14th Armored Division, there was a little more fighting and liberating, and some dying, left to be done.[33] Postscript In its advance across Germany, the 14th Armored Division liberated approximately 200,000 Allied prisoners of war from German captivity. Among them were more than 30,000 Americans or about forty percent of the total number held in Germany.[34] The division also liberated some 250,000 "displaced persons," as well as the large Dachau sub-camp at Ampfing. Shortly after the end of the war, the nickname "LIBERATORS" was suggested for the division in an article which appeared in Army Times.[35] Understandably, the nickname stuck, and "LIBERATORS" became the division's official nickname.[36] Author's Comments The author wishes to thank James F. Kneeland, Ray F. Lohof, Samuel R. Glenn, Robert A. Allwein, John Sawyer, Charles Franklin, and Col. Bob E. Edwards, former commanding officer of the 68th Armored Infantry Battalion, for sharing their experiences, and expanding on their personal memories and observations during interviews. Daniel R. Gentry deserves special recognition for sharing with the author, his clear, unvarnished recollections and observations of the events which occurred at the Combat Command A command post on 29 April, 1945. A special debt is owed to Col. George England Jr., former commanding officer of the 94th Cavalry Reconnaissance Squadron, who so generously shared with the author his vast knowledge of the 14th Armored Division's combat history and its personnel, and for guiding the author to those veterans who could best relate the events surrounding the liberation of Stalag VIIA. The author also wishes to thank Lt. Gen. Arthur P. Clark for his time and patience in answering the author's questions about his experiences "inside the wire" at Stalag VIIA. Any errors contained in this article are the sole responsibility of the author. End Notes 1. The New York Times, 30 April, 1945, Section A, p. 3 and 1 May, 1945, Section A, p. 4. 2. 12th Army Group; Situation Maps, 28 and 29 April, 1945. 3. Historical Report, 47th Tank Bn., April 1945.; Historical Report: 94th Cavalry Squadron (Mechanized), April 1945.; History: 125th Armored Engineers Bn., p.89; History of the 68th Armored Infantry Bn., p.32.; Combat Command A: History; European Operations, p.17. The 68th AIB was attached to CCA when it crossed the Danube River, but late on 28 April the battalion, minus C Company, was attached to CCR in preparation for an attack on the city of Landshut. 4. The strength estimate is based on data from, Stanton, Shelby L. World War II Order of Battle, (Galahad Books, New York) 1984. p. 18. 5. Combat Command A: History, p. 17.; Highly Mobile "A": The Combat History of Headquarters and Headquarters Company, Combat Command "A", p. 6. 6. Interview with author: James F. Kneeland, 20 June, 2005. Mr. Kneeland was a squad leader in the 2nd Platoon, B-68. 7. Ibid. Mr. Kneeland recalls that the units at the roadblock had been warned to expect a vehicle flying a white flag, and not to fire on it.; Combat Command A: History, p. 21. 8. Interviews with author: Lt. Gen. Albert P. Clark, 16

June and 8 July, 2005. Gen. Clark, was a Lt. Col. during

WWII. He was the second most senior American officer at Luft

III, and later at Stalag VIIA. Gen. Clark served as the

Intelligence/Security officer in both camps. According to

Gen. Clark, Group Captain Willets is sometimes confused with

a Group Captain Kellet, who was also a prisoner at Stalag

VIIA.; Interviews with author: Daniel R. Gentry, 20 June and

7 July, 2005. At the time in question, Mr. Gentry held the

rank of Major, and was the Intelligence Officer (S-2) of

Combat Command A. Due to an unusual set of circumstances, he

also functioned as the Operations Officer (S-3). Mr. Gentry

was present in the CCA command post during the entire time

that the delegation was there, and was involved in the later

discussions regarding Gen. Smith's orders and the impending

attack on Moosburg. According to Mr. Gentry, Willets was the

Group Captain who traveled to CCA Headquarters with the

delegation.; Combat Command A: History, 9. Combat Command A: History, p. 21.; Interview with author: Daniel R. Gentry, 20 June and 7 July, 2005. Mr. Gentry recalls that this sort of intelligence often did not reach the division level, and its lack contributed to the frequent "surprises" experienced by the advancing units. 10. "Peep" was used by the U.S. Armored Forces instead of the more common term, "jeep." 11. Interviews with author: Daniel R. Gentry, 20 June and 7 July, 2005. 12. MacDonald, Charles B., The Last Offensive, (GPO, Washington), 1972, pp. 418-19. 13. 47th Tank Battalion: History from New York o/Hudson to Muhldorf o/Inn., (Druck von Geiger, Muhldorf) 1945, p. 35. 14. Interview with author: Charles A. Franklin, 2 July, 2005.; Mr. Franklin served in C Battery, 500th AFA. 15. Interview with author: James F. Kneeland, 20 June, 2005. 16. Ibid.; 47th Tank Battalion History, p. 37. 17. Durand, Arthur A., Stalag Luft III: The Secret Story, (Touchstone, New York) 1989., p. 353.; Clark, Albert P., 33 Months as a POW in Stalag Luft III, Fulcrum, Golden, CO) 2005., p. 173.; Interview with author: James F. Kneeland, 20 June, 2005. Prior to crossing the bridge over the Amper River, Mr. Kneeland recalls being cautioned by a superior not to fire to the left because stray rounds might go into the prison camp. Evidently, the admonition was promptly forgotten when the SS troops opened fire from behind the railroad embankment. 18. Carter, History of the 14th Armored Division.; 47th Tank Battalion: History, p. 37. The size of the SS force which defended the town is unknown, but 6,000 German soldiers, including many SS, were taken prisoner at Moosburg. 19. Interview with author: James F. Kneeland, 20 June, 2005.; Interview with author: Robert A. Allwein, 11 June, 2005. At Moosburg, Mr. Allwein was the Asst. Driver of the tank which nearly slid off the bridge into the Isar River. 20. Durand, Stalag Luft III: The Secret Story, p. 353. 21. Combat Command A: History, pp. 22. 22. Ibid., p. 22.; Major Gustov Simoleit, the Assistant Commandant of the camp, presided over the surrender of the prison guards. 23. Ibid., p. 22. 24. Ibid., p. 22.; History of the 14th Armored Division. Both sources state that there were 27 Russian generals at Stalag VIIA. In his book, Lt. Gen. Clark gives the number as "about ten," and includes a photo of ten Russian generals taken after the liberation. (pp. 178-179.) 25. Carter, History of the 14th Armored Division. 26. 47th Tank Battalion: History, p. 37. 27. Combat Command A: Historical Report, April 1945, p. 8. 28. Interviews with author: Daniel R. Gentry, 20 June and 7 July, 2005. 29. Combat Command A: History, p.22. This source states that according to "German estimates" the number Allied POWs was 110,000.; Interviews with author: Lt. Gen. Albert P. Clark, 16 June and 8 July, 2005. Only about 30,000 POWs were held in the main camp (stammlager). The majority, who were enlisted men and NCOs, were held in temporary camps in the immediate area of Moosburg, and were used as workers on farms, factories, and construction projects in the area between Landshut and Munich. 30. U.S. Air Force Oral History Interview; Lt. Gen. Albert P. Clark, 20-21 June, 1979. Albert F. Simpson Historical Research Center, Office of Air Force History, Headquarter USAF, Washington, p.127..; Interview with author: Lt. Gen. Albert P. Clark, 16 June and 8 July, 2005. Gen. Clark believes that it is impossible to know the exact number of American POWs at Moosburg, but he thinks 30,000, "is a good number."; Carter, History of the 14th Armored Division . 31. Combat Command A: History, p.21; 32. Carter, History of the 14th Armored Division. 33. Ibid. The 14th Armored Division moved quickly forward, and establish two bridgeheads across the Inn River before the end of the war. 34. The total number of American prisoners of war officially reported in enemy hands at the end of the war was 75,034. (Statistical Review, World War II: A Summary of ASF Activities, Headquarters, Army Service Forces, Washington, 1945, p. 157.) 35. Army Times, Vol. 6, No. 8, 29 September, 1945, p.15. 36. The list of Army units with officially authorized Special Designations (nicknames) can be seen at: http://www.army.mil/CMH-PG/lineage/SpcDes-123.htm .; The 14th Armored Division is also recognized as a "Liberation Unit" by the U.S. Memorial Holocaust Museum.

|

| Last update 27 Sep 2006 by © Team Moosburg Online (E-Mail) - All rights reserved! | |||